Y Combinator’s Asia influence fades despite India gains

Y Combinator continues to generate outsized returns from companies with roots in India even as its broader influence across Asia shows signs of long-term retreat, reflecting a strategic shift by the world’s best-known startup accelerator amid changing regional dynamics. While founders from Bengaluru, Chennai and Delhi remain visible in its demo days and alumni rosters, the programme no longer shapes Asia’s startup narrative in the way it once did. Founded in 2005 in Silicon Valley, Y Combinator built its reputation by backing early-stage companies that later became global giants, including Airbnb, Stripe and Dropbox. Its appeal in Asia peaked during the previous decade, when limited access to global capital and mentorship made association with a US-based accelerator especially valuable. India emerged as one of the biggest beneficiaries, with dozens of YC-backed startups securing follow-on funding, overseas market access and high-profile exits. Companies such as Razorpay, Meesho and Groww, all of which passed through the YC ecosystem in earlier years, became reference points for founders seeking validation from global investors. India’s expanding pool of engineers, rising digital adoption and a large domestic market aligned well with YC’s software-first investment philosophy. These successes continue to deliver financial returns for the accelerator through equity stakes that have appreciated sharply as several firms reached unicorn valuations or prepared for public listings. Yet the accelerator’s footprint across Asia has narrowed. YC formally closed its China-focused efforts earlier in the decade, citing regulatory complexity and difficulties operating within a tightening policy environment. Activity in Southeast Asia also slowed, with fewer batches featuring startups from Indonesia, Vietnam or Thailand compared with earlier years. The shift reflects not only YC’s internal priorities but also the maturation of Asia’s startup ecosystems, which now offer more local alternatives. Across Asia, domestic accelerators, corporate venture arms and sovereign-backed funds have stepped in to fill gaps once dominated by Silicon Valley programmes. In India, initiatives backed by large conglomerates, universities and state governments provide capital, mentorship and market access without requiring relocation or deep integration into the US ecosystem. Southeast Asia has followed a similar path, with regional venture firms increasingly willing to lead early rounds. YC itself has changed. The accelerator has leaned further into its core strengths, focusing on fewer geographies while doubling down on artificial intelligence, developer tools and enterprise software. Its decision to emphasise remote participation during and after the pandemic reduced the symbolic value of spending months in Silicon Valley, a factor that once set YC apart for Asian founders. While remote access broadened participation, it also diluted the sense of exclusivity that helped the programme stand out. For Indian startups, the relationship with YC has become more transactional. Participation is still seen as a strong signal of quality, especially for companies targeting global markets or US-based customers. However, founders increasingly view YC as one of several possible launchpads rather than a defining milestone. Follow-on funding now depends less on accelerator pedigree and more on unit economics, regulatory clarity and the ability to scale within complex local markets. Investors tracking Asia’s venture landscape note that YC’s reduced presence does not imply a loss of relevance everywhere. India remains an exception because of its scale, talent depth and ongoing pipeline of software-led startups with global ambitions. YC partners continue to engage with Indian founders, and each batch includes a steady, if smaller, number of companies from the country. Returns from earlier bets ensure that India remains financially meaningful to the accelerator. At the same time, YC no longer sets the pace for Asia-wide innovation trends. Local accelerators and venture funds are shaping sectors such as fintech, climate technology and logistics, areas where regulatory nuance and on-the-ground execution matter as much as global networks. Governments across the region have also become more involved in startup promotion, offering grants, sandboxes and procurement opportunities that reduce reliance on foreign programmes. The article Y Combinator’s Asia influence fades despite India gains appeared first on Arabian Post.

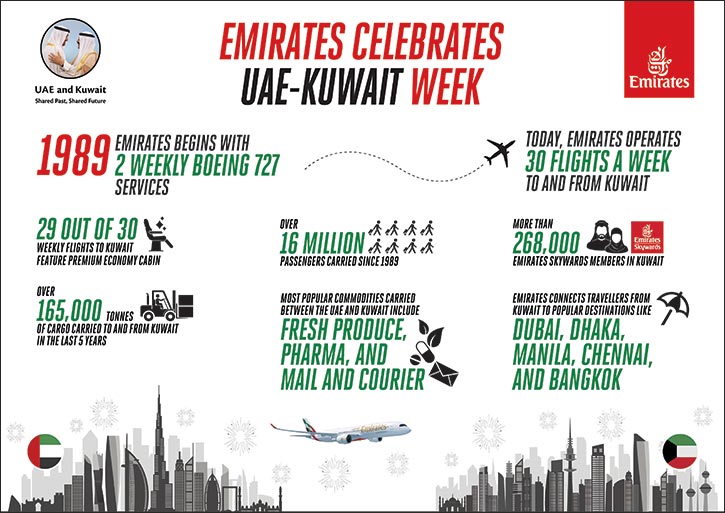

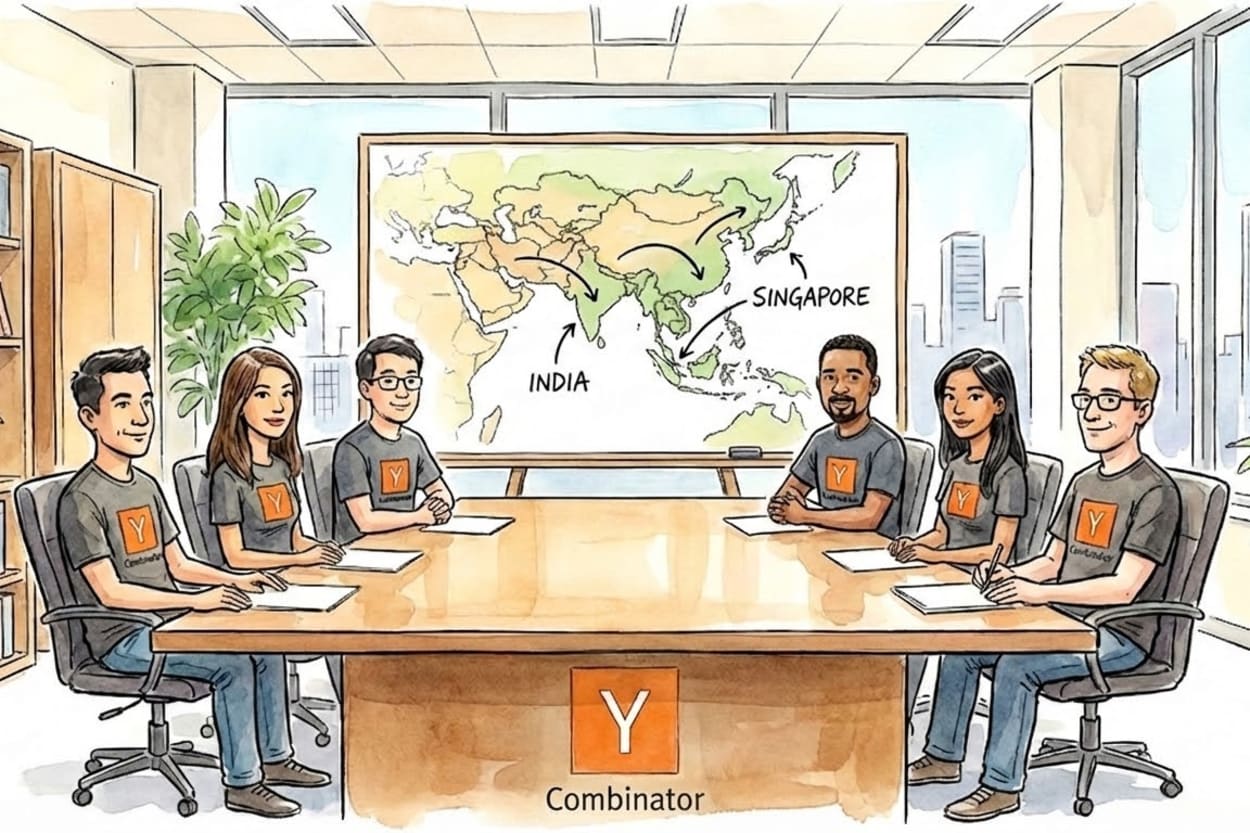

Y Combinator continues to generate outsized returns from companies with roots in India even as its broader influence across Asia shows signs of long-term retreat, reflecting a strategic shift by the world’s best-known startup accelerator amid changing regional dynamics. While founders from Bengaluru, Chennai and Delhi remain visible in its demo days and alumni rosters, the programme no longer shapes Asia’s startup narrative in the way it once did.

Founded in 2005 in Silicon Valley, Y Combinator built its reputation by backing early-stage companies that later became global giants, including Airbnb, Stripe and Dropbox. Its appeal in Asia peaked during the previous decade, when limited access to global capital and mentorship made association with a US-based accelerator especially valuable. India emerged as one of the biggest beneficiaries, with dozens of YC-backed startups securing follow-on funding, overseas market access and high-profile exits.

Companies such as Razorpay, Meesho and Groww, all of which passed through the YC ecosystem in earlier years, became reference points for founders seeking validation from global investors. India’s expanding pool of engineers, rising digital adoption and a large domestic market aligned well with YC’s software-first investment philosophy. These successes continue to deliver financial returns for the accelerator through equity stakes that have appreciated sharply as several firms reached unicorn valuations or prepared for public listings.

Yet the accelerator’s footprint across Asia has narrowed. YC formally closed its China-focused efforts earlier in the decade, citing regulatory complexity and difficulties operating within a tightening policy environment. Activity in Southeast Asia also slowed, with fewer batches featuring startups from Indonesia, Vietnam or Thailand compared with earlier years. The shift reflects not only YC’s internal priorities but also the maturation of Asia’s startup ecosystems, which now offer more local alternatives.

Across Asia, domestic accelerators, corporate venture arms and sovereign-backed funds have stepped in to fill gaps once dominated by Silicon Valley programmes. In India, initiatives backed by large conglomerates, universities and state governments provide capital, mentorship and market access without requiring relocation or deep integration into the US ecosystem. Southeast Asia has followed a similar path, with regional venture firms increasingly willing to lead early rounds.

YC itself has changed. The accelerator has leaned further into its core strengths, focusing on fewer geographies while doubling down on artificial intelligence, developer tools and enterprise software. Its decision to emphasise remote participation during and after the pandemic reduced the symbolic value of spending months in Silicon Valley, a factor that once set YC apart for Asian founders. While remote access broadened participation, it also diluted the sense of exclusivity that helped the programme stand out.

For Indian startups, the relationship with YC has become more transactional. Participation is still seen as a strong signal of quality, especially for companies targeting global markets or US-based customers. However, founders increasingly view YC as one of several possible launchpads rather than a defining milestone. Follow-on funding now depends less on accelerator pedigree and more on unit economics, regulatory clarity and the ability to scale within complex local markets.

Investors tracking Asia’s venture landscape note that YC’s reduced presence does not imply a loss of relevance everywhere. India remains an exception because of its scale, talent depth and ongoing pipeline of software-led startups with global ambitions. YC partners continue to engage with Indian founders, and each batch includes a steady, if smaller, number of companies from the country. Returns from earlier bets ensure that India remains financially meaningful to the accelerator.

At the same time, YC no longer sets the pace for Asia-wide innovation trends. Local accelerators and venture funds are shaping sectors such as fintech, climate technology and logistics, areas where regulatory nuance and on-the-ground execution matter as much as global networks. Governments across the region have also become more involved in startup promotion, offering grants, sandboxes and procurement opportunities that reduce reliance on foreign programmes.

The article Y Combinator’s Asia influence fades despite India gains appeared first on Arabian Post.

What's Your Reaction?