Giant crocodiles once stalked Sahara rivers and dinosaurs

Towering crocodilians that could rival buses in length once patrolled vast river systems cutting through what is now the Sahara, reshaping scientific understanding of prehistoric ecosystems and predator–prey dynamics during the early Cretaceous Period. Fossil evidence shows these reptiles were not merely oversized versions of today’s crocodiles but apex predators capable of taking on large dinosaurs in a landscape unrecognisable from the modern desert. The most striking […] The article Giant crocodiles once stalked Sahara rivers and dinosaurs appeared first on Arabian Post.

Towering crocodilians that could rival buses in length once patrolled vast river systems cutting through what is now the Sahara, reshaping scientific understanding of prehistoric ecosystems and predator–prey dynamics during the early Cretaceous Period. Fossil evidence shows these reptiles were not merely oversized versions of today’s crocodiles but apex predators capable of taking on large dinosaurs in a landscape unrecognisable from the modern desert.

The most striking example is Sarcosuchus imperator, a colossal crocodilian whose remains were uncovered in the Ténéré region of Niger. Excavations at the start of the 21st century revealed roughly half of one individual’s skeleton, allowing researchers to reconstruct an animal estimated to have stretched close to 12 metres and weighed up to eight tonnes. The sheer scale of the find earned it the informal nickname “SuperCroc” and cemented its status as one of the largest crocodilians ever known to science.

Although fragments of Sarcosuchus had been identified decades earlier, the Ténéré discoveries transformed fragmented knowledge into a coherent biological picture. Multiple specimens from the same geological horizon, dated to about 110 million years ago, showed consistent traits that set the species apart from both living crocodiles and other prehistoric relatives. These animals had elongated skulls lined with robust, conical teeth arranged to grip and subdue massive prey, rather than the fish-specialised dentition seen in many modern river crocodiles.

Palaeontologists say this tooth structure strongly suggests a diet that extended beyond fish and small vertebrates. Large herbivorous dinosaurs that frequented riverbanks would have been vulnerable, particularly juveniles or individuals forced to cross waterways. Bite-mark analysis and comparisons with modern crocodilian behaviour indicate ambush attacks from the water, with prey seized at the shoreline or mid-crossing before being dragged under.

Anatomy supports this ambush-predator interpretation. The eyes and nostrils of Sarcosuchus were positioned high on the skull, allowing the animal to remain almost entirely submerged while watching and breathing. This configuration mirrors that of living crocodilians, but on a far grander scale. Once concealed in murky water, a fully grown Sarcosuchus could strike with little warning, using sheer mass and jaw power to overwhelm animals many times larger than most modern crocodile prey.

Growth patterns further underscore how these giants came to dominate their ecosystems. Bone studies indicate that Sarcosuchus continued growing throughout much of its life, unlike many reptiles whose growth slows markedly after maturity. The largest individuals were likely several decades old, possibly living for half a century or more. This prolonged growth allowed survivors of early life stages to reach sizes at which few predators posed a threat.

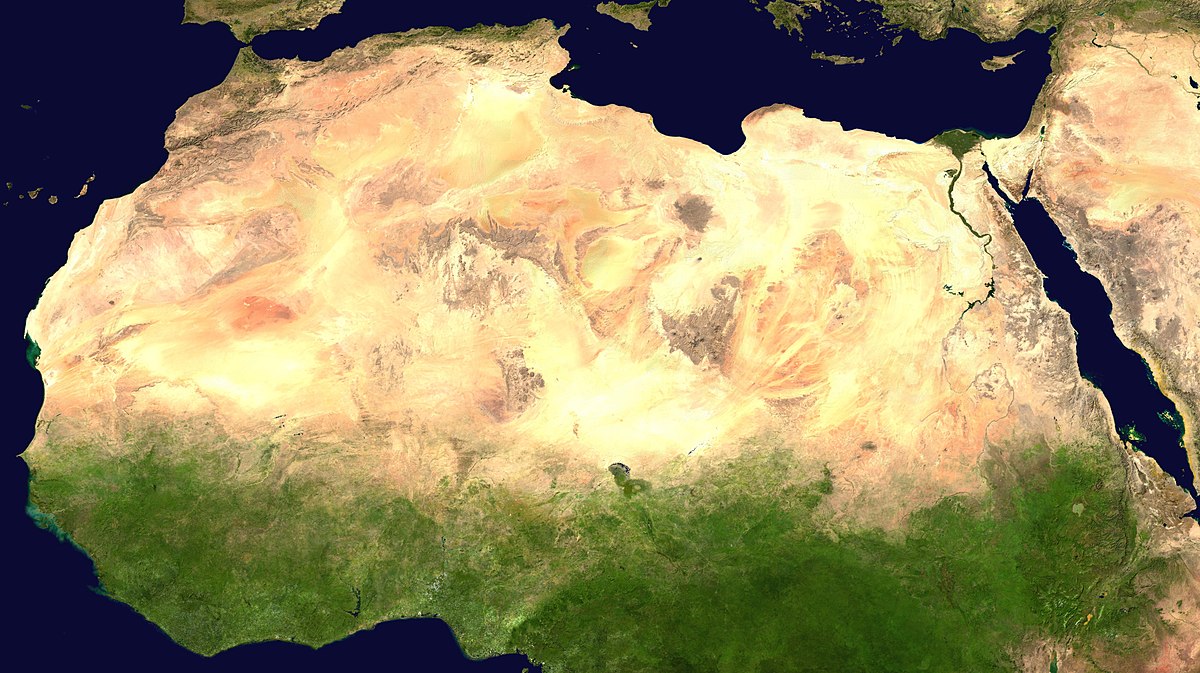

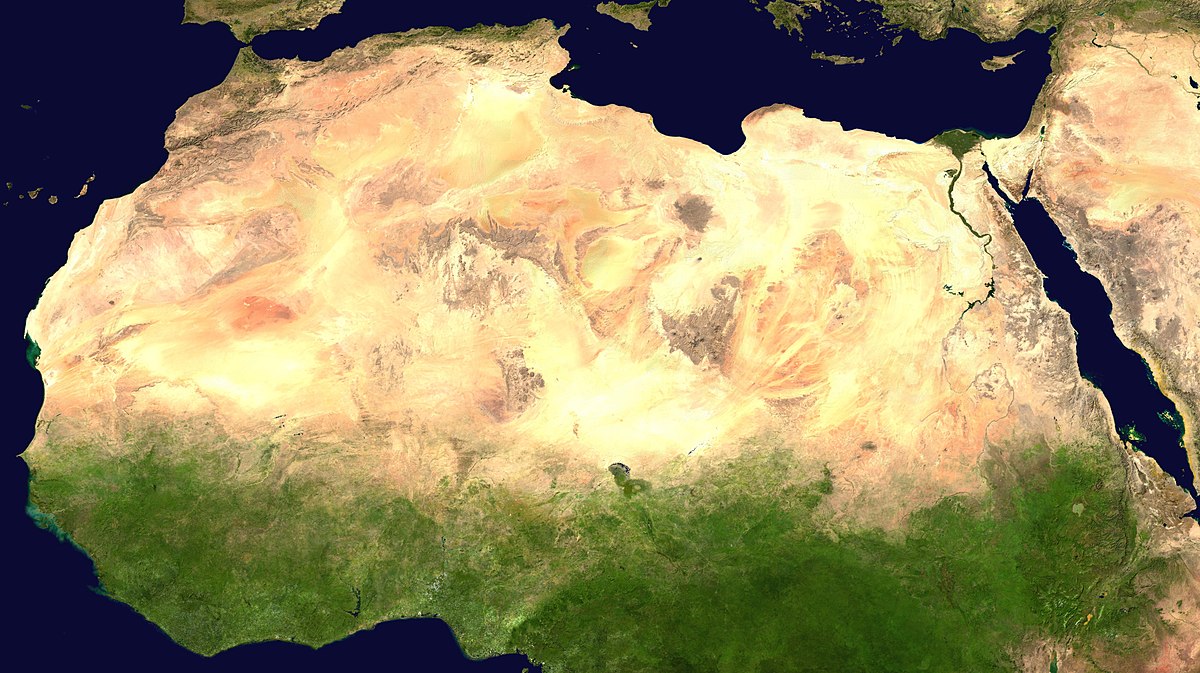

The environment that sustained such enormous reptiles contrasts sharply with today’s Sahara. Geological and fossil evidence shows the Ténéré region was once a humid tropical landscape crisscrossed by broad rivers and floodplains. Dense vegetation, abundant fish and herds of dinosaurs created a food web capable of supporting multiple giant crocodilians within the same drainage systems. Sediment layers indicate slow-moving waterways deep enough for animals of Sarcosuchus’s size to manoeuvre and hunt effectively.

Despite their fearsome reputation, these predators were not invincible. Their massive bodies, while advantageous in water, limited agility on land. Researchers believe Sarcosuchus was poorly suited to sustained movement away from rivers, reducing its ability to chase prey across open ground. Dinosaurs that kept their distance from waterways, or moved in groups, may have lowered their risk of attack.

The article Giant crocodiles once stalked Sahara rivers and dinosaurs appeared first on Arabian Post.

What's Your Reaction?