ICE Taps into School Security Cameras to Aid Trump’s Immigration Crackdown

This story was co-published with The Guardian. Police departments across the U.S. are quietly leveraging school district security cameras to assist President Donald Trump’s mass immigration enforcement campaign, an investigation by The 74 reveals. Hundreds of thousands of audit logs show police are searching a national database of automated license plate reader data, including from school […]

This story was co-published with The Guardian.

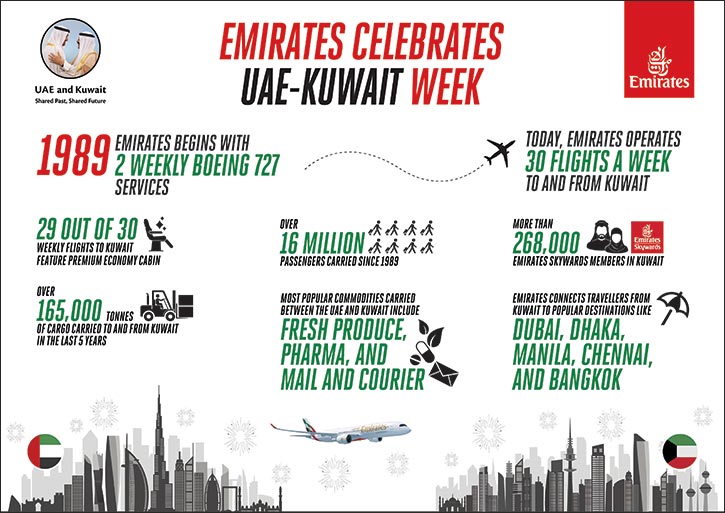

Police departments across the U.S. are quietly leveraging school district security cameras to assist President Donald Trump’s mass immigration enforcement campaign, an investigation by The 74 reveals.

Hundreds of thousands of audit logs show police are searching a national database of automated license plate reader data, including from school cameras, for immigration-related investigations.

The audit logs originate from Texas school districts that contract with Flock Safety, an Atlanta-based company that manufactures artificial intelligence-powered license plate readers and other surveillance technology. Flock’s cameras are designed to capture license plate numbers, timestamps and other identifying details, which are uploaded to a cloud server. Flock customers, including schools, can decide whether to share their information with other police agencies in the company’s national network.

Multiple law enforcement leaders acknowledged they conducted the searches in the audit logs to help the U.S. Department of Homeland Security enforce federal immigration laws, with one saying the local assist was given without hesitation. The Trump administration’s aggressive DHS crackdown, which has grown increasingly unpopular, has had a significant impact on schools.

Educators, parents and students as young as 5 have been swept up, with immigrant families being targeted during school drop-offs and pick-ups. School parking lots are one place the cameras at the center of these searches can be found, along with other locations in the wider community, such as mounted on utility poles at intersections or along busy commercial streets.

The data raises questions about the degree to which campus surveillance technology intended for student safety is being repurposed to support immigration enforcement, whether school districts understand how broadly their data is being shared with federal agents and if meaningful guardrails exist to prevent misuse.

“This just really underscores how far-reaching these systems can be,” said Phil Neff, research coordinator at the University of Washington Center for Human Rights. Out-of-state law enforcement agencies conducting searches that are unrelated to campus safety but include school district security cameras “really strains any sense of the appropriate use of this technology.”

Flock devices have been installed by more than 100 public school systems nationally, government procurement records show, and audit logs from six Texas school districts show campus camera feeds are captured in a national database that police agencies across the country can access. School district Flock cameras are queried far more often by out-of-state police officers than by the districts themselves, according to the records.

School police officers use Flock cameras to investigate “road rage,” “speeding on campus,” “vandalism” and “criminal mischief,” records show. There is no evidence school districts themselves use the devices for immigration-related purposes — or that they’re aware other agencies do so.

Research by UW’s human rights center and reporting by the technology news outlet 404 Media previously revealed that police agencies nationwide were tapping into Flock camera feeds to help federal immigration officials track targets. In some cases, local law enforcement agencies enabled direct sharing of their networks with U.S. Border Patrol.

Immigration officials’ unprecedented use of surveillance tactics to carry out their controversial mission has faced sharp criticism. That school district cameras are part of that dragnet has not been previously reported.

Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, called the revelation an “egregious end run around the Constitution” that will add to the pressure on Congress to rein in U.S. Customs and Immigration Enforcement. By accessing campus feeds, she said, immigration authorities are violating the rights of students, parents and educators “to be free from unreasonable search and seizure.”

The teachers union sued the Trump administration in September after it ended a longstanding policy against conducting immigration enforcement actions in and around schools and other “sensitive locations.”

“Schools are sacred spaces — and ICE knows it needs a judicial warrant to access them,” Weingarten said in a statement. The teachers union filed its lawsuit, she said, “so schools remain safe and welcoming places, not targets for warrantless surveillance and militarized raids.”

‘The scale of it is phenomenal’

At the Huffman Independent School District northeast of Houston, records reveal it was the campus police chief’s administrative assistant who granted U.S. Border Patrol access to district Flock Safety license plate readers in May.

Police departments nationwide also routinely tapped into the eight Flock cameras installed at the 30,000-student Alvin Independent School District south of Houston. Over a one-month period from December 2025 through early January, more than 3,100 police agencies conducted more than 733,000 searches on the district’s cameras, The 74’s analysis of public records revealed. Of those, immigration-related reasons were cited 620 times by 30 law enforcement agencies including ones in Florida, Georgia, Indiana and Tennessee.

Flock offers a list of standardized reasons that agencies must choose from when running a search. For the Alvin school district’s cameras, immigration-related reasons identified by The 74 include “Immigration (civil/administrative)” and “Immigration (criminal).”

The data put into focus the scale of digital surveillance at school districts nationally and “just how dangerous these tools are,” said Ed Vogel, a researcher and organizer with The NOTICE Coalition: No Tech Criminalization in Education.

“The scale of it is phenomenal, and it’s something that I think is difficult for individual people in their cities, towns and communities to fully appreciate,” said Vogel, who’s also with the surveillance-monitoring Lucy Parsons Labs in Chicago.

The Flock camera audit logs and other public records about their use by school districts were provided exclusively to The 74 by The NOTICE Coalition, a national network of researchers and advocates seeking to end mass youth surveillance. The 74 also filed public records requests to obtain information on schools’ use of Flock cameras and conducted an analysis to reveal the extent of the immigration-related searches. Those findings were shared with the law enforcement agencies and school districts mentioned in this story.

Three of the 10 agencies that conducted the most immigration-related searches in the Alvin school district logs participate in the 287(g) program, which deputizes local officers to perform certain immigration enforcement functions and has also become a point of controversy. The program has grown by 600% during Trump’s second term.

Alvin school district Police Chief Michael Putnal directed all questions to district spokesperson Renae Rives, who provided public records to The 74 but did not acknowledge multiple requests for comment.

Amanda Fortenberry, the spokesperson for the Huffman school district, said in an email the district is “reviewing the matters you referenced,” but declined to comment further.

Flock Safety, which operates some 90,000 cameras across 7,000 networks nationally, didn’t respond to The 74’s requests for comment, nor did the Department of Homeland Security.

‘We will assist them — no questions asked’

Camera settings information obtained by The 74 through public records requests suggests that Alvin school district police officers are unable to search their own devices for immigration-related purposes. But the school system allows such queries routinely from out-of-state police officers, audit logs reveal.

Flock searches for civil immigration reasons that appeared in the Alvin school logs, such as trying to locate someone who is unlawfully present in the U.S., were more than two times more frequent than those conducted for investigations involving immigrants suspected or convicted of committing a crime.

Also included among the reasons given for immigration-related searches are “I.C.E.,” in reference to Immigration and Customs Enforcement, “ERO proactive crim case research,” an apparent reference to ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations division and “CBP Investigation,” an apparent reference to U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

In Carrollton, Georgia, officers routinely use Flock’s nationwide lookup to track suspects outside their jurisdiction, Lt. Blake Hitchcock said in an interview. Immigration-related searches that appear in the Alvin school district’s audit log by the Carrollton Police Department were conducted to assist federal agents at the request of the Department of Homeland Security, Hitchcock said. He declined to elaborate on specifics.

Federal agents “were working directly” with a Carrollton police officer who had access to the Flock cameras “and they asked him to run it and they did,” Hitchcock said. If federal agents ask his office to help them with an immigration case, Hitchcock said, “we will assist them — no questions asked.”

Flock searches are typically broad national queries, and officers do not select individual cameras, he explained. Instead, with each search request, the system automatically checks every camera that Flock customers share with the nationwide database, including those operated by school districts.

Because a school district is part of the national lookup, Hitchcock said, its cameras will be searched any time another participating agency conducts a nationwide inquiry. He said Flock’s nationwide search is helpful to track people who “go from jurisdiction to jurisdiction to commit crimes.” He pointed to a high-profile child abduction case in 2020 when Carrollton officers used Flock cameras to rescue a 1-year-old who was kidnapped at gunpoint some 60 miles away.

In Galveston, Texas, Constable Justin West confirmed that immigration-related searches that appeared in the Alvin school district’s audit logs from his department were tied to the county’s participation in the federal 287(g) program.

County deputies with federal immigration enforcement powers “have been working on arresting targeted criminal illegal aliens,” West wrote in an email, and use Flock cameras “to determine locations and travel patterns of the illegal aliens being sought.”

Galveston deputies’ Flock searches that appeared in the Alvin school district audit logs led to several arrests, West said, while several of the investigations remain ongoing. Flock logs show the Galveston County searches were conducted for both criminal and civil immigration investigations.

While the Trump administration maintains its immigration crackdown centers on removing dangerous criminals, ICE arrests of people without criminal records surged to 43% in January. U.S. citizens and immigrants with no pending civil immigration actions against them have similarly been detained.

Other agencies that participate in the 287(g) program that were heavily represented in the Alvin ISD logs include the Texas Department of Public Safety and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, each of which conducted more than 60 immigration-related searches that queried the school district’s cameras in the one-month period.

The Texas Department of Public Safety and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission were among four agencies that did not respond to The 74’s inquiries about their searches. The other two were the Lowndes County Sheriff’s Office in Georgia and the Greene County Sheriff’s Office in Ohio.

In Mesquite, Texas, searches labeled “Immigration (criminal)” were “conducted as part of an investigation to locate a suspect wanted on felony criminal charges,” Lt. Curtis Phillip said in an email. While the suspect “was believed to be unlawfully present in the United States,” Phillip said his department doesn’t use Flock cameras “for the purpose of enforcing federal civil immigration law.”

“When a search is conducted across the shared network, the activity may appear in the audit records of all participating system owners, even when the investigation itself is unrelated to schools or school-based activity,” Phillip said. “There is no efficient mechanism to exclude specific entities, such as school districts, from those searches.”

In Grant County, Indiana, 238 immigration-related searches included in the Alvin ISD audit logs were conducted “by one of our deputies” as part of “a confidential investigation,” Jay Kay, chief deputy of the county sheriff’s office, said in an email. He didn’t elaborate further. The reason given for the search in the Flock audit log was “Immigration (civil/administrative) – Test.”

It’s not clear whether every search tagged as immigration-related necessarily was. John Samples, captain of the Little Elm, Texas, police department, said a detective selected “immigration” as a search reason while assisting the Department of Homeland Security on a sex crimes investigation and a separate terrorism-related case. That word choice, Samples said, was “not the best course of action” and will be “corrected on our end.”

The police department in Texas City, Texas, denied it used the system to enforce federal immigration laws. While the agency monitors “several thousand Flock Cameras across the United States,” Captain Brandon Shives said his department’s searches in the Alvin ISD logs should not have been categorized as immigration-related and that it was the result of a “clerical error.”

‘Your community and beyond’

Flock Safety has repeatedly stated that it does not provide the Department of Homeland Security with direct access to its cameras and that all data-sharing decisions are made by local customers, including school districts.

“ICE cannot directly access Flock cameras or data,” the company said in a recent blog post. “Local public safety agencies sometimes collaborate with federal partners on serious crimes such as human trafficking, child exploitation or multi-jurisdictional violent crime,” but decisions about “how data is shared are made by the customer that owns the data, not by Flock.” “You know how maybe your grandparents approve every friend request they get on Facebook? It’s like that. It’s always been like that.”Dave Maass, investigations director, Electronic Frontier Foundation

The company acknowledged in August it ran pilot programs with the DHS to assist federal human trafficking and fentanyl distribution investigations but that “all ongoing federal pilots have been paused” after the initiative faced scrutiny and legal pushback.

Public records provided by the Alvin school district, which began purchasing Flock cameras in 2023 and has since spent more than $50,000 on its eight devices, include Flock marketing materials that tout the ability to share data with other police agencies.

“Not only do we place cameras where you need them,” the document notes, “we offer access to available cameras in your community and beyond your jurisdiction.”

In fact, nationwide sharing is a staple of Flock’s business model, said Dave Maass, director of investigations at the nonprofit Electronic Frontier Foundation. Maass has spent the last decade researching how police use automated license plate readers like Flock to track protesters and, in at least one case last year, investigate a woman for having an abortion in Texas, where the procedure is illegal.

“That’s something that’s a selling point for them,” Maass said, adding that his research has shown that police agencies agree to provide outside officers access to their Flock data with little deliberation.

“You know how maybe your grandparents approve every friend request they get on Facebook?” Maass said. “It’s like that. It’s always been like that. You’ll have an agency that will request access to other places and other places will just not even question it. They’ll just hit ‘sure, approve.’”

‘A unique level of responsibility to protect their students’

Flock Safety provides audit logs that allow law enforcement customers to see how their automated license plate reader cameras are being used. The reports “support accountability and public trust by making usage patterns visible and reviewable,” the company said in the recent blog post.

None of the law enforcement officials contacted by The 74 said they used the audit logs to ensure people with access to their data queried the information for legitimate and legal purposes. Given the overwhelming volume of law enforcement searches that are included in the Alvin school district audit logs in just a month, Maass said, such reviews would be practically impossible.

Adam Wandt, an attorney and associate professor at New York City’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice, said license plate readers can be invaluable tools for solving serious crimes and finding missing persons.

But he also acknowledged the devices present significant privacy concerns and questioned whether the broad sharing of school-controlled camera data violates federal student privacy rules. The revelation that school-owned Flock cameras are being queried for immigration enforcement purposes, he said, “will cause significant discussions to be had in the near future within many school districts” that contract with the company.

“School districts are in a unique position, they have a unique level of responsibility to protect their students in specific ways,” including their privacy, Wandt said.

Vogel of the NOTICE Coalition said students and parents should demand transparency from their school districts about whether they employ Flock license plate readers and whether the data from those cameras are being fed to immigration agents.

“These are just tools, and whoever has control over them gets to define how they’re used,” Vogel said. “I have a feeling that immigration enforcement was not one of the reasons that was discussed when they said, ‘We need to get a contract with Flock Safety.’”

What's Your Reaction?