How UAE built first homegrown rocket after 2 years of trial and error

Two minutes before launch, engineers were still rewriting telemetry code. Then the countdown began, and the launchpad fell silent.For the Technology Innovation Institute’s team, the successful flight of the UAE's first homegrown hybrid rocket was the result of more than two years of simulations, supplier trial-and-error, and painstaking system integration, culminating in a moment of collective relief when the rocket split cleanly in two and drifted back to Earth under parachute.The project began with assembling a deliberately mixed team. “We put together experienced experts and young talent, and we established a clear roadmap,” said Dr Elias Tsoutsanis, chief researcher at TII’s Propulsion and Space Research Centre. Early on, the group identified risks linked to manufacturing and supply chains, particularly because components were being produced at prototype scale rather than mass production.Stay up to date with the latest news. Follow KT on WhatsApp Channels.“For this kind of technology, suppliers had to adapt their capabilities to produce components for new applications,” he explained, describing what he called a learning process for both engineers and manufacturers. The decision to proceed with local manufacturing, he added, ultimately paid off by enabling a fully locally manufactured system.Technology Innovation Institute teamFrom there, the work moved into extensive testing. “We had to design a very thorough test procedure with multiple iterations,” Tsoutsanis said. This included simulations, repeated ground tests of the rocket motor, integration with the launch pad and multiple firing trials while the rocket was already mounted.Before liftoff, every system had to be verified. Control, hydraulic and telemetry systems were tested and retested, with troubleshooting and system integration becoming central to the effort. “System integration itself is a project of its own,” he said later, noting that its complexity is often underestimated and cannot be fully replicated through simulations.The rocket was backed by a team of 15 propulsion, aerospace, mechanical, electrical and software engineers, as well as computer science specialists. Several team members were UAE nationals, each responsible for specific systems such as telemetry, control paths, launch pad operations and software to operate valves and sensors.One of the earliest challenges was determining whether local suppliers could meet the precision required for prototype components. “We had to iterate several times in order to reach the level of quality that we wanted,” Tsoutsanis said, describing close collaboration with manufacturers to refine parts before integration. Advanced materials researchers also played a key role, helping manufacture carbon-fibre components that provided structural strength to the rocket.LiftoffAs launch day approached, pressure intensified. With a fixed target date, the team often discovered additional work that needed to be done late in the process. “When you reach close to launch, you realise that you need to do extra work because something might not have been taken into consideration.”The most emotionally charged moment came just before liftoff. “If you observe people involved in a rocket launch, especially before the countdown starts, you see that everyone is in silence,” Tsoutsanis described. “They go into their own mood, fingers crossed, hoping everything goes well.”Relief followed once the rocket left the launch pad and telemetry confirmed it was meeting altitude specifications. But the defining moment came later, during recovery. At its highest point, the rocket separated into two sections connected by a parachute. Visual confirmation from onboard cameras showed both parts descending safely. “When we saw the parachute and the two pieces floating, there was a very strong feeling of relief.”Recovery was critical. “For us, it was very important to recover all parts of the rocket in order to record the data, verify performance and make sure everything went as planned.”Not all risks were technical. Ignition timing, he explained, allowed only a narrow window of a few seconds for systems to align correctly. Telemetry was another major concern. “Telemetry is like the brain of the rocket system,” he said, noting that every component had to communicate reliably while the rocket was operated remotely.Even minutes before launch, work was still ongoing. “Two minutes before the launch, we were coding and verifying aspects of the telemetry,” Tsoutsanis recalled, calling it one of the moments that stood out most to him.From concept to flight, the project took just over two years. That time was spent refining objectives, identifying suppliers, running tests and building the infrastructure needed to support the launch.Looking ahead, Tsoutsanis described the mission as a first step. Using flight data from this test, the team plans to scale the rocket to higher altitudes and larger payloads, enabling more demanding experiments and, eve

Two minutes before launch, engineers were still rewriting telemetry code. Then the countdown began, and the launchpad fell silent.

For the Technology Innovation Institute’s team, the successful flight of the UAE's first homegrown hybrid rocket was the result of more than two years of simulations, supplier trial-and-error, and painstaking system integration, culminating in a moment of collective relief when the rocket split cleanly in two and drifted back to Earth under parachute.

The project began with assembling a deliberately mixed team. “We put together experienced experts and young talent, and we established a clear roadmap,” said Dr Elias Tsoutsanis, chief researcher at TII’s Propulsion and Space Research Centre. Early on, the group identified risks linked to manufacturing and supply chains, particularly because components were being produced at prototype scale rather than mass production.

Stay up to date with the latest news. Follow KT on WhatsApp Channels.

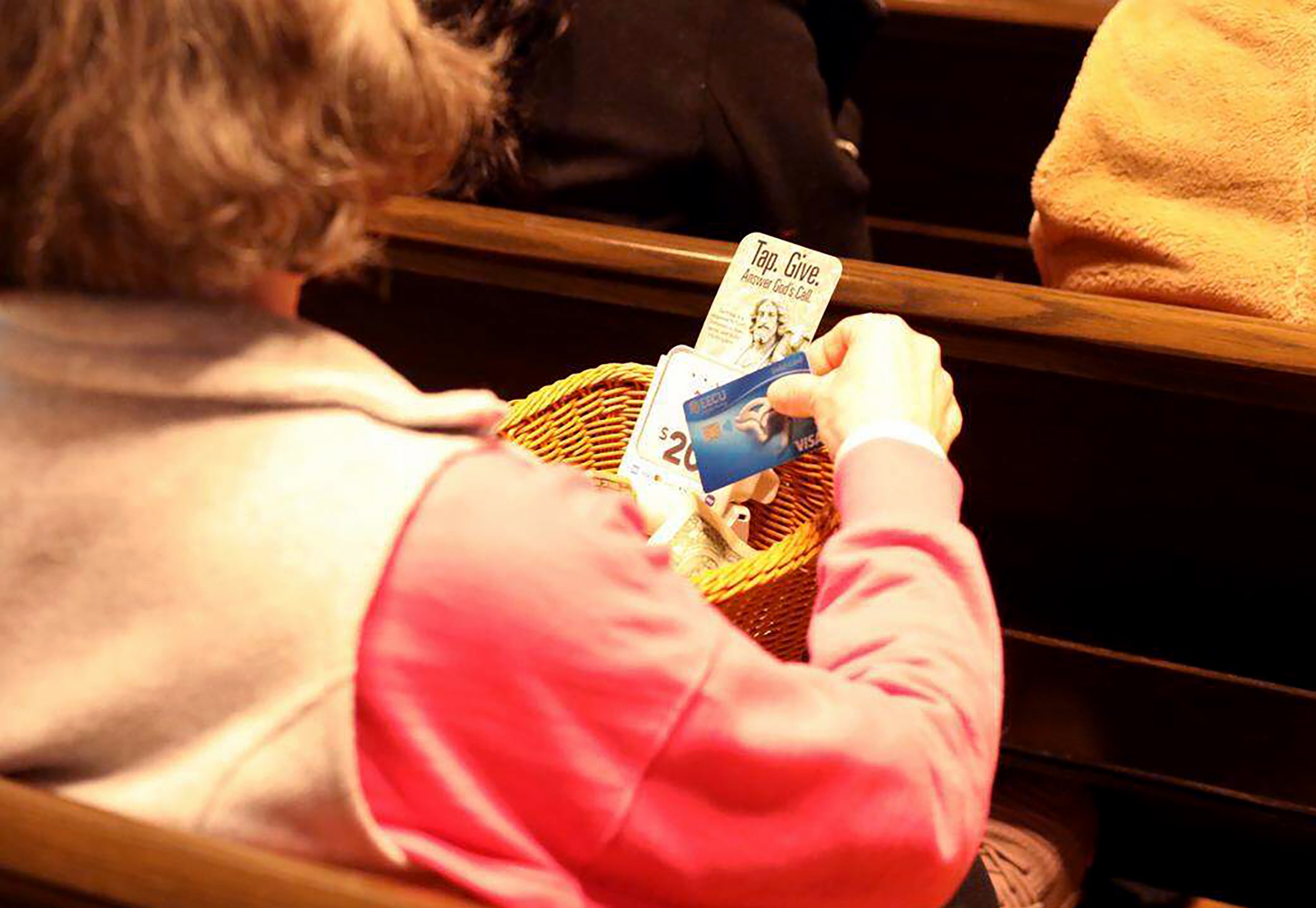

“For this kind of technology, suppliers had to adapt their capabilities to produce components for new applications,” he explained, describing what he called a learning process for both engineers and manufacturers. The decision to proceed with local manufacturing, he added, ultimately paid off by enabling a fully locally manufactured system. Technology Innovation Institute team

From there, the work moved into extensive testing. “We had to design a very thorough test procedure with multiple iterations,” Tsoutsanis said. This included simulations, repeated ground tests of the rocket motor, integration with the launch pad and multiple firing trials while the rocket was already mounted.

Before liftoff, every system had to be verified. Control, hydraulic and telemetry systems were tested and retested, with troubleshooting and system integration becoming central to the effort.

“System integration itself is a project of its own,” he said later, noting that its complexity is often underestimated and cannot be fully replicated through simulations.

The rocket was backed by a team of 15 propulsion, aerospace, mechanical, electrical and software engineers, as well as computer science specialists.

Several team members were UAE nationals, each responsible for specific systems such as telemetry, control paths, launch pad operations and software to operate valves and sensors.

One of the earliest challenges was determining whether local suppliers could meet the precision required for prototype components.

“We had to iterate several times in order to reach the level of quality that we wanted,” Tsoutsanis said, describing close collaboration with manufacturers to refine parts before integration. Advanced materials researchers also played a key role, helping manufacture carbon-fibre components that provided structural strength to the rocket. Liftoff

As launch day approached, pressure intensified.

With a fixed target date, the team often discovered additional work that needed to be done late in the process. “When you reach close to launch, you realise that you need to do extra work because something might not have been taken into consideration.”

The most emotionally charged moment came just before liftoff. “If you observe people involved in a rocket launch, especially before the countdown starts, you see that everyone is in silence,” Tsoutsanis described. “They go into their own mood, fingers crossed, hoping everything goes well.”

Relief followed once the rocket left the launch pad and telemetry confirmed it was meeting altitude specifications. But the defining moment came later, during recovery. At its highest point, the rocket separated into two sections connected by a parachute.

Visual confirmation from onboard cameras showed both parts descending safely. “When we saw the parachute and the two pieces floating, there was a very strong feeling of relief.”

Recovery was critical. “For us, it was very important to recover all parts of the rocket in order to record the data, verify performance and make sure everything went as planned.”

Not all risks were technical. Ignition timing, he explained, allowed only a narrow window of a few seconds for systems to align correctly. Telemetry was another major concern. “Telemetry is like the brain of the rocket system,” he said, noting that every component had to communicate reliably while the rocket was operated remotely.

Even minutes before launch, work was still ongoing. “Two minutes before the launch, we were coding and verifying aspects of the telemetry,” Tsoutsanis recalled, calling it one of the moments that stood out most to him.

From concept to flight, the project took just over two years. That time was spent refining objectives, identifying suppliers, running tests and building the infrastructure needed to support the launch.

Looking ahead, Tsoutsanis described the mission as a first step. Using flight data from this test, the team plans to scale the rocket to higher altitudes and larger payloads, enabling more demanding experiments and, eventually, contributing to future launch vehicle development.

“Sounding rockets naturally evolve into boosters,” he explained, outlining a long-term path toward small satellite launch capability.

What's Your Reaction?